A week in the Basque Country

These mountains look like they were lifted from an alien world that plausibly follows most of our same laws of physics, of uniformitarianism, of orogeny

There was no gate available for our small regional jet at the Bilbao airport so we stopped well short of the terminal and the air handling system shut down and the cramped cabin immediately became stuffy with the thick breath and hot heat of the passenger mass as we waited for the portable stairs to arrive. There was a soft murmured foundation of private conversation except for three tall guys in their twenties in the back pretty much yelling over each other excitedly in a language I didn’t recognize. It was disorienting. It was probably Basque.

Jess and I had both slept on and off during this short flight from Madrid, the third and final leg of a trip that started fourteen hours earlier in Buffalo. We were bleary eyed, tired, and irritable after the disorienting accelerated nighttime of an easterly transatlantic red eye. I was starting to get a little nauseous.

After stooping to finally exit the airplane I stood on the top step and felt instantly refreshed. The Bilbao airport is in a long, narrow valley that opens northwest towards the Bay of Biscay. The valley is formed by steep, green forested slopes and there were thick, low clouds hanging well below the ridge tops giving the tarmac the feeling of a vast, softly cotton-ceilinged room with distant green textured walls. The ground was wet and reflective from a recent rain and it made the entire surface of the earth look uniform and pristine. The air was cool, neither dry nor humid, and held a vague tint of marine brine. My clammy skin and nausea evaporated, my heavy eyelids lifted. As we waited on the tarmac for our gate-checked bags I took deep breaths and slowly turned around and around to take in this miraculous feeling of recuperation. I smiled hugely at Jess and said something about a bowl of fog and she gave me a generous smile.

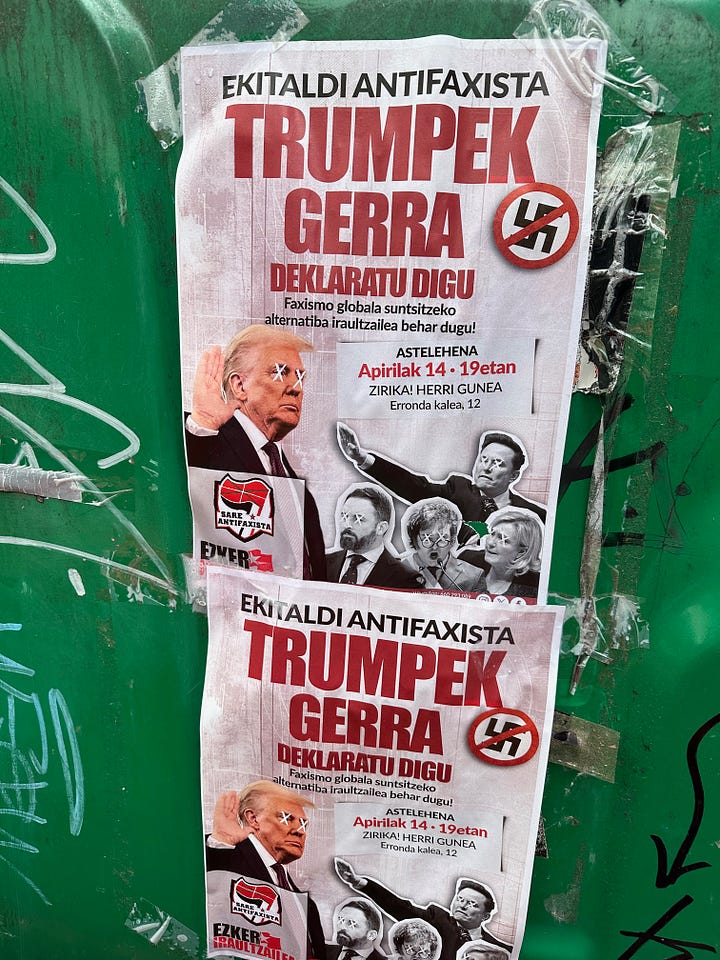

The Basque Country is too complicated to describe fully here, but it is broadly considered to be the eastern most corner of Spain’s north coast along the Bay of Biscay and a small piece of southwest France. It includes the cities of Bilbao, Vitoria-Gasteiz, Pamplona, San Sebastian, and Bayonne, but the modern Basque Autonomous Community includes just three states in Spain - Gipuzkoa, Biscay, and Álava - which excludes France and Pamplona. The Basque language is widely used on public and private signage and is commonly spoken now - a proudly celebrated rebirth after centuries of suppression, most recently in the middle decades of the last century under Franco’s “unified” vision for Spain. Franco made Castilian Spanish the official and only language of the country; speaking Basque was outlawed. He declared regional southern things like paella and Flamenco axiomatically “Spanish,” and worked to eliminate all other regional particulars.

In an interesting and macabre side note, Guernica is in the Basque country, the town bombed by the Nazis in 1937 at Franco’s request to help defeat the Basque resistance during the Spanish Civil War, an event memorialized famously by Picasso. This painting is on display, somewhat ironically, in the Reina Sofia museum in Madrid. Our last full day in Spain was spent in Madrid just to see this painting, actually, as it had long been on Jess’ “list.” We also spent a very crowded hour in the Prado to see some of my favorite paintings - Goya’s black series - and we snuck a look at Las Meninas.

Basque is unrelated to any other extant language and is thought to be one of the last living versions of a pre-Indo-European neolithic tongue. The Basque term for the Basque country is Euskal Herria and the language is Euskara. The Basque people are Euskaldun. Cider is sagardoa and freedom is askatasun.

There was a significant violent conflict from 1959 to 2011 between the ETA - Euskadi Ta Askatasuna (Basque Country and Liberty) - and the Spanish national government. The IRA and Sinn Fein collaborated with the ETA in “resistance tactics” in the 1970s and 80s and they have also worked together more recently in peace negotiations with the Spanish government - the two movements clearly share a narrative.

In 2001, after graduating college, I traveled to Europe for nearly a month with two childhood friends, Ben and Mike. San Sebastian was a place we chose to visit because of Hemingway, of course (The Sun Also Rises), and it was our favorite stop on that trip, better than Dusseldorf, Amsterdam, Barcelona, Alicante, Seville, Cordoba, and Madrid. But things seem to have changed so much since then - as far as I can tell from my two short visits - San Sebastian has become much more developed, commercial, cleaner, busier, and more expensive and I wonder if that had anything to do with the ETA peace process. We were vaguely aware of the violence in the Basque country in 2001, but I don’t recall worrying about it much at all.

I’m sure it was on the minds of the residents of San Sebastian at that time. Gregorio Ordóñez Fenollar was gunned down in 1995 by the ETA in La Cepa, a restaurant in the old city of San Sebastian. La Cepa is just two doors down from Bar Martinez where Jess and I enjoyed our last evening in town this past April. Ordóñez was a member of the Basque Parliament, the Deputy Mayor of San Sebastian, and was running for Mayor at the time of his killing. Froilán Elespe Inciarte, a city council member in Lasarte-Oria about five miles south of San Sebastian and less than a mile from Zapiain cidery, was shot and killed at a bar in Lasarte by an ETA assassin on March 30th, 2001.

While we were completely unaware of it at the time, 2001 was filled with ETA attacks and near-misses, of bombs detonated and defused, of shootings inside and outside of the Basque country. In fact, there were at least two incidents while we were in San Sebastian that summer - the home of an Ertzaintza officer (Basque state police) was bombed and two bombs were defused at a bank in the city. There was also an attack gone-wrong close to where we were in the southern city of Alicante - “July 24: An ETA militant accidentally blows herself up in Torrevieja, Alicante. The blast injured seven people.”

Bilbao is the largest city in the Basque Country and reminded me and Jess of Pittsburgh in a lot of ways - built on a river, steep ridges, winding and confusing roads, a funicular (which we rode), and a cultural rebirth following decades of industrial decline. A woman working the front desk at our hotel in Bilbao, after asking us where we were from and only vaguely understanding when we said, “about equidistant from Buffalo, Cleveland and Pittsburgh” - told us that she had spent a week in Pittsburgh once while driving from NYC to LA - “I was staying in a cool neighborhood with bars that had hamburgers and beer.”

Tapas are the famous “small plates” from Spain - pretty much snacks you eat with drinks. Pintxos are the tapas of the Basque Country - they are usually larger, more elaborate, held together with a wooden skewer, often with a piece of baguette. The word comes from the verb “to skewer” or “prick.” You can make a meal of pintxos and bars get creative with them. The pintxos in Bilbao were not as good as they were in San Sebastian, in our limited experience. There were plenty of good ones, and a couple creative ones, we found some good ones in Plaza Nueva, particularly Victor Montes (also the only place I was engaged about my Phillies hat in a meaningful way by a local), but the “croqueta” is the standard pintxo in Bilbao and while they are OK, they are an example for me of what I find a little boring and common about Spanish cuisine - salty, fatty, creamy, mushy, breaded, fried, served on or with bread. Another example of this kind of pan-European vibe is that they really love mayonnaise in Spain and put it on almost everything. I’ve seen ‘em do it. They fuckin’ drown ‘em in that shit.

The mouthfeel of a croquette is like eating wet, half-baked bread dough and there is rarely anything acidic, spicy, or otherwise contrasting to offset the salt and fat and mush. I guess that’s what the wine is for? The pintxos de croquetas de calamares en su tinta are interesting - squid croquettes in their ink - little dark purple logs - but in terms of flavor they just add a fishy note and the color only goes so far to make it interesting. The kimchi croquetas I had at a stand in the Ribera Market were the best we tried, they had some acid and funk, though the artificial green color was off-putting.

My favorite pintxo in Bilbao was rabas - fried squid - which isn’t quite a traditional pintxo, but it was common in Bilbao bars. Rabas are only served on certain days, apparently, and there were little signs in bars - “Hay rabas” - “there are rabas” - to indicate they were available. As a Spanish language learner I was oddly frustrated with this phrase - surely it should have been some quirky reflexive construction like “se disponible rabas” or “se sirve rabas” that I’ve come to expect from things like “se renta” or “se habla espanol”, but no, it’s the perfectly literal and obvious “there are rabas.” Breaded and deep fried squid in Bilbao is made of thick chunks or strips of undistinguished squid flesh that are meaty and juicy and much heartier than the thin rings of calamari in the US.

After two days of Bilbaoan pintxos and not wanting traditional Spanish food, aka a giant chuleta or a Michelin starred seafood restaurant, we were on the hunt for pizza. We found a place that looked great - pizza and calzones advertised as traditional and made by Italians. The photos looked awesome. It was out of the tourist area of the Casco Viejo and the Guggenheim and I was excited to walk through some “real” neighborhoods, though even the touristy neighborhoods of Bilbao and San Sebastian don’t feel that touristy. We climbed steeply up the hill from the Nervión River and through the San Francisco neighborhood behind the Abando train station. It was full of immigrants, Moroccan restaurants, and halal shops. It’s supposed to be a bad neighborhood but we didn’t feel unsafe at all.

A few blocks after crossing the train tracks we stopped in Zabalburu Plaza for a few drinks. This is a very busy intersection of six different major streets. The “square” is actually round and this should probably be a roundabout like every other intersection of this size seems to be in Europe, but I’m glad this one isn’t. The northern radius of the “square” is a wide and comfortable sidewalk where cafes had their tables and between this sidewalk and the intersection is a tiny city park with almost dune-like sloped and curving waves of grey square pavers that shore up soil that holds trees and shrubs. There are two small fountains. This parklet was dirty with litter and debris, the typical drifts of small square paper napkins that are common throughout the city. Though it was a very fine place to take a vermouth, a wine, and a beer.

We moved on a few blocks to the pedestrian only Egana Street to further stimulate our appetite with vermouth and finally landed at Pizzería Formaggi Bilbao. We highly recommend it. We had to try two pizzas and a calzone, in addition to the burrata al forno appetizer, so we had leftovers. It was about 9pm when we left the restaurant and started to make our way back to our hotel. Before we hit Zabalburu we knew something was happening - the crowds on the street were positively thick and we could see a crowd of people eight or ten deep lining the east side of the plaza. There were police cars and barriers blocking the other roads into and out of the intersection. As we got closer we could see it was a massive religious procession and it was creeping down the road - the hundreds of penitent brothers clad in their different colored hoods walking slowly and seriously, the blaring of their horns in a dour minor melody barely hanging together and the clacking of their drums interspersed between the stanzas sounded serious and sad. Bilbao’s Semana Santa processions date back to 1554 when a splinter from Christ’s Cross arrived in the city and the first penitent brotherhood was formed - the Brotherhood of the True Cross.

The procession was moving south and we tried to force our way north on the sidewalk through the throngs, I had to hold the pizza box above my head so I could squeeze through the crowd, but it was very slow going and finally some people forcing their way south said it was at least an hour walk to get around that way so we turned around and returned to our seats from earlier on the sidewalk by the little park and sat with vermouth and beer and our pizza box and watched the procession and the people.

The Basque Country is rugged and mountainous, though the western edge of the Pyrenees is included only in the historical, more broadly construed understanding of the region. There are several distinct mountain ranges in Biscay and Gipuzkoa outside of the Pyrenees and we planned two different days to explore them. We rented a car in Bilbao at the train station and departed for Urkiola National Park, about twenty miles southeast of Bilbao near the town of Durango. Urkiola principally comprises a northwest to southeast trending range of limestone massifs that have been each wholly cantilevered into fantastic and exotic inclinations and weathered into oddly smooth and round shapes yet still boast frighteningly abrupt rocky precipices. These mountains look foreign, like they were lifted from an alien world that plausibly follows most of our same laws of physics, of uniformitarianism, of orogeny. Jesús María Pedrosa Urquiza, a city council member in Durango, born in Ordizia, was gunned down in the streets of Durango after church on Sunday June 4th, 2000 by an ETA assassin.

The walk to Mugarra (3,070’) from the valley floor is mostly on a private road then a two track that eventually makes some rocky switchbacks before the high pass just west of the peak is gained. It is only two miles to the pass, but over 2,000’ of elevation. Mugarra has a high, rugged exposed vertical rock face that is spectacular, but for me the best part of the hike was hiking around Eskuagatx (3,290’) in the distance. This mountain is a flat piece of limestone nearly a mile long from north to south and half a mile wide from east to west. It is rounded on a thousand foot radius on its northwestern edge and tilted nearly forty five degrees to the east as if the surface of the earth was designed to open here on a hinge to create a ramp. It is ringed with beech trees and a uniform scrub forest clings to its tabletop surface half way up until they succumb to exposure and give way to bare rock.

Anboto is at the far southeastern edge of this range, just a few miles from Mugarra, and is the highest peak in Urkiola at 4,367’. In ancient Basque mythology Anboto is said to be the home of Mari - a pre-christian deity whose closeness in name to Mary probably made it easier for some Basque to “undertake veneration of the Virgin Mary.”

It was exceptionally windy on Mugarra and we scurried back down a few switchbacks to sit on a boulder and eat our leftover pizza. We drank a can of San Miguel beer and a can of Coke and listened to the sheep grazing above us and the clanking of a cowbell in the distance. Vultures soared near the cliff face and I like to think they were bearded vultures that eat mostly bone and are fascinating in so many other ways but we weren’t sure.

The pintxos of San Sebastian are reason enough to visit this small city on this spectacular bay, La Concha. The Parte Vieja, the old town, is a pedestrian warren of bars and restaurants and shops - dense and busy enough to occupy several nights of exploration despite its small area. We stopped at Casa Vergara on the first night. It’s located just across the street from The Basilica of Saint Mary of Coro, a baroque church built in 1774. Casa Vergara has an art deco vibe and excellent pintxos. We first tried chorizo cooked in cider here. We came back twice more while we were in San Sebastian just because it was familiar and we could always manage to get a seat. While it wasn’t our favorite pintxo spot, we did love it. We hit a few other spots that night including Federiko where Jess had her first ration of mushrooms, which became a bit of a theme.

The next morning we loaded up on impeccable pastry at Galparsoro Okindegia and wheeled the red Peugeot rental sedan out of the city and towards the little coastal town of Deba, about ten miles as the crow flies to the west of San Sebastian, but a drive of nearly an hour. I hated that rental car. It wouldn’t stop telling us when we were speeding and when we were entering and leaving low emissions zones. Sure, I did get a speeding ticket - by that time I was completely ignoring the car’s alerts. We were heading to Deba to see the flysch rock beach and cliffs - flysch is finely repeated layers of sedimentary rocks that look like hard corduroy. Here they have been uplifted and turned by tectonic activity and are exposed on this section of rugged coast.

We took the even slower, windier, and more picturesque coastal route back to San Sebastian. It was a fantastically beautiful sunny day but was chilly in the shade. We stopped in a small town on the coast called Zumaia for lunch and had the only bad interaction of the whole trip with a bartender who made fun of my Spanish - mocking the way I said - “Hablas muy rapido. ¿Puedes hablar mas lento, para mi?” He repeated it in a mocking way and laughed at me and gestured to an old guy at the bar and he laughed. He seemed like a genuine dick though I realize what I said is not good Spanish. I apologized and told him in Spanish that I can read Spanish OK, and speak a little, but it is difficult to understand “habladores nativos.” I made a sorry face as I explained it. I think he was impressed that I could speak that much Spanish, though I’m sure I fucked that up, too, and he seemed to ultimately feel bad and he shook my hand seriously and said something to me quickly that I didn’t understand and then seemed to recommend the tripe. I wonder if he spoke Basque? Either way we left that place and had a wonderful lunch just around the corner at a place called Idoia where the bartender and server bravely humored my bad Spanish. After several Pinxtos and appetite stimulating beers and vermouths I enjoyed braised beef cheeks and Jess grilled octopus. On August 8th, 2000, José María Korta Uranga, president of the Gipuzkoan employers’ association, was murdered by the ETA with a car bomb in Zumaia for refusing to pay the extortionary “revolutionary tax.” A month later the ETA blew up his brother’s bar in Deba, too.

We made reservations for txotx at Zapiain. Txotx is the cider tasting and meal that happens from January to April in the Basque country. Historically it was when bars, restaurants, and really anybody who wanted to purchase a large amount of cider could come and select their lots of cider from the large wooden vessels where it is aged after primary fermentation for three to four months. The cider purchasers would bring food to eat during their tastings and make a party. The food was always cod omelette, chorizo cooked in cider, and chuleta - thick cut rib steaks, txuleton, cooked very rare and heavily salted.

There are maybe a hundred cideries, sagardotegis, in the Basque country, and Zapiain is one of the most respected and well known. I was expecting this to be a tourist experience but it was not. Our txotx had maybe sixty or seventy people, a full house at Zapiain, and they all appeared to be local or with some connection to the area judging by the way they greeted the cider maker, the servers, each other. There was no English being spoken and plenty of Basque. I guess this had to do with it being Semana Santa. We asked our server and she said that every night is different but that this was mainly locals. She said that a couple days earlier it was mainly tourists.

The cider maker historically yelled “txotx” when he was ready to open a new barrel, or kupela in Basque, and everyone would gather around. These barrels are large, probably five or ten thousand liters, and in the US we’d call them foeders, I suppose. I was disappointed to never hear the cider maker yell txotx, but he opened every one of the twelve or so kupelas that were full. He would place an empty glass on the cross member over the head of the barrel when we moved to the next. I’m not sure on the exact meaning of “txotx,” I’ve heard it means “to speak” and also “stick,” and it refers to the wooden spile that stoppers the cask. When the spile is pulled a thin stream of cider arcs out and is “caught” by each person, one after another, in their glass, just a few fingers worth, sometimes ten or twenty people will be lined up and it’s a bit of choreography to all get a sample in the tight cellar without letting the cider run onto the floor.

The prevailing wisdom is that you need to aerate the cider in your glass to get the right flavor experience. If serving Basque cider from a bottle, it is said to be “thrown” into the glass as it is poured from a height of two or three feet. The Zapiain bottles have a plastic insert in the neck to promote a turbulent, aerated pour. I suppose the turbulent txakoli wine pour is done for the same reason. The distinctive Basque wine, txakoli, while quite dry and acidic, is much “cleaner” than Basque cider and far easier to drink on its own, in our opinion.

Every barrel of cider we tasted was a little different, the thing I noticed varying the most was the level of apple flavor intensity, but they were all bracingly acidic and funky and tannic. They all showed some acetic character. The blended, bottled cider that was served with the txuleton was a little more balanced, but still bracing. I would have a hard time regularly drinking Basque cider on its own - it’s just too intense - but I have to say it is a perfect accompaniment to food - particularly the rich, fatty and salty food of the Basque region - the cod with pil pil sauce, an emulsification of olive oil and garlic, the chorizo, the beef. The txuleton is supposedly a rib steak, but it was cut in a manner I was unfamiliar with and it was actually quite lean for a rib steak.

We spent a day in Irun and visited the Oiasso Roman Museum where there is an excavated Roman bath house in addition to a large collection of artifacts. I was particularly drawn to the Roman fish hook collection. Driving into and out of Irun, right on the border with France, we cannot recommend. We sat in traffic in the middle of a weekday for a long time and I got my speeding ticket right as we finally hit open road and I let that Peugot eat.

We lucked into an outdoor standing table at Gandarias in San Sebastian later that evening. The town was significantly more crowded than the night before and way more crowded than Tuesday night. Gandarias has some of the best pintxos we found - pintxo de ternera, pintxo de solomillo de ternera, and the risotto with truffle and basque sheep’s cheese, idiazabal, were the highlights, though the latter is technically a “ración.” The crowd was growing to overwhelming proportions in the restaurant, but the professional bartenders made the ordering experience smooth every time I went back to refresh our beverages and order a few pintxos while Jess held down the table.

The crowd was thick in the streets, too, mostly Spanish tourists, it seemed, in town for Semana Santa. The table next to us opened up and a large extended family quickly grabbed it. The tables here are small tables convenient for two or maybe three people as they are pushed up against the restaurant’s wall on one side and the crush of the crowd on the other. The young mother and father with their baby in a stroller, the grandparents and an uncle, I assume, and a slightly older mom with a slightly older kid all crowded up to the table, bracing themselves against the flow of the crowd on the street. The grandfather and uncle were dispatched for drinks and pintxos and returned with hands full and their small table quickly overflowed and Jess pointed at our table and indicated that he could set his beer down to make room. After she had finished her identical beer she nearly picked his up a couple times.

We hiked Txindoki on Good Friday along with what seemed like every other person in the Basque Country. It was absolutely swarmed. Txindoki is probably the most famous and emblematic mountain of the Basque Country. It is physiographically distinct - its rocky crest, reaching over 4,400’, appears like the heavy blade of a splitting maul - long and thin and curving but growing quickly down into a very thick base. In Basque mythology it is said to be one of the secondary homes of Mari. Traditionally, Basque women who wish to become pregnant place a pebble from their home at the mouth of Mari’s cave at the summit of Txindoki.

This mountain is located in the Aralar Range deep in southeastern Gipuzkoa and forms the border between Gipuzkoa and Navarre. A thing I like about the Basque country is that their modern manner of dress is very similar to our American style - jeans, sneakers, hiking boots, flannels, hoodies, Patagonia Nano Puff lookalikes, shades of blues and greens and earth tones, even ball caps. It is not a stylish place outside of pockets of San Sebastian, which has always been stylish. This may have helped us blend in a bit. Nearly every hiker that morning greeted us with a “kaixo” or, much more commonly, “aupa!”. “Kaixo” is the first Basque word you learn and it means “hello.” We were doling out kaixos pretty heavily on the trail and I think this ultimately betrayed us as non-Basque. “Aupa” is a more casual greeting and means “hey” or in the trail or sports context it can mean cheerful and enthusiastic encouragement: “come on!” or maybe in modern American slang - LFG! Hundreds of people gave us an “aupa!” and that was really cool. Whether they thought we were Basque or that’s just what you say when you hike Txindoki, we found it welcoming. This also helped us make sense of the drunk grandpa’s exclamations outside Zapiain two nights earlier - frustrated by his sick grandson ruining his Semana Santa txotx - the kid was rushed out by his mother and he puked across the street in the bushes - grandpa came out ten minutes later bellowing “aupa!” over and over as he slowly and reluctantly followed his family to the parking lot.

We made it near the summit, to the second to last switchback before the summit where several unauthorized trails run straight up the steep scree slope. We could see several groups of twenty or thirty people snaking up the final switchback as well as several other groups scurrying up the scree. The crowds, and because the hiking was hard - the trail was deeply rutted and very rocky - was enough to make us turn around. On the way down we were lucky enough to see a large Iberian emerald lizard - nearly a foot long and quite thick, with a finely pointillist and textured iridescent green and black pattern all over its body except the large triangular head is smooth. Jess was excited to discover thousands of blooming Fritillaria below the tree line. These flowers are not native to western New York where we live or to anywhere in the eastern US, though Jess cultivates some in our gardens. The plant is a bulb-forming perennial that produces a small, almost inflated looking flower that nods dramatically from a single green stem and lasts for just a few days every spring. They are exquisitely beautiful and there are a few native species in this part of the Basque Country. These were purple and mottled purple and green.

After getting off Txindoki we drove the narrow and very winding roads to the small town of Ordizia, tucked into the valley of the Oria River in the steeply wooded hills. We went to the Tximista cidery. It is a small cidery located right next to the river. Five large kupelas sit on a concrete floor just off the large open dining room. There was a young man, maybe in his early twenties, setting up for the day’s txotx, placing table settings at long tables with long benches. Otherwise it was empty and silent. I told him in my broken Spanish that we had been learning about Basque cider and we were hoping to try some of their cider. He asked “only a taste?” And I said yes, just a taste. I apologized for not knowing any more Basque than “sagardoa.” He took two of the cañas from the table setting he was working on and handed them to us and walked over and opened the tap on the barrel and threw the cider into our glasses and then returned to his work.

We milled around looking at the apple press and the fermenters and sipped the cider. The cider was nearly identical to Zapiain, to our untutored senses, big apple flavor, bone dry, and full of hard acid, tannins, and acetic notes. We thanked the guy and I offered him a five euro note and he refused it. I said it was just a tip and thanked him again and he refused again, this time a little insulted, and he said it was nothing to share some cider and he thanked us for visiting. He asked where we were from and he said he wants to visit New York.

We walked out to the bridge over the river Oria and Jess immediately spotted two fish hanging in the current just upstream rising to eat something off the surface. They were big, maybe two feet long, and looked like trout to me. Then we saw a third fish glide out from the eddy and join them in their irregular though structured feeding, holding just like big trout, eating just like big trout. I was very excited. We took turns watching them though Jess’ polarized sunglasses. A man and a woman walked behind us on the bridge and slowed down and saw what we were looking at and I said to them, “¿Hay truchas?” The man laughed and told me in Spanish that they were not trout, that there are trout in the river but further up where the current is faster and it's colder and that it was too dirty for trout in Ordizia. The woman laughed at this and shook her head. He said they were barbels and indicated with his finger the slender, fleshy whisker-like sensory organs that protrude from the sides of their mouths. I said, “¿peces gatos?” and he laughed and said “no, barbel, barbel!” And they walked away. When I googled it I found that they are a game fish and fly anglers target them in this river, one of the best in the area, apparently.

It was a warm, sunny day and we took a stroll through Barrena Park before leaving. It was shady and pleasant and we sat on a bench by a long rectangular fountain just below a branch of the Official School of Languages. There are fourteen campuses across the Basque country, all part of the Autonomous Basque Community public school system. Ordizia is where María Dolores González Katarain was murdered by the ETA in the public square in front of her three year old son in 1986. Ordizia was her hometown. She was an ETA member who participated in armed terrorist actions in the 1970s and was said to be one of the highest ranking women in the group. She had abandoned the ETA after spending time in prison in France in exchange for a pardon from the Spanish government and she lived in exile in Mexico for several years before returning to Spain where she was labeled a traitor by the ETA. After her murder many Basque people spoke out against the group - hardline Basque who believed in independence. Her killing marked a significant turning point in their history.

That last night in San Sebastian, after bumping around a couple spots in the old city, we were lucky enough to get bar seats at Bar Martinez. I think their pintxos were the best we had on the trip. They were creative, beautiful, and showed interesting and diverse flavors. My favorite was a creamy shredded crab mixture somehow with cod and topped with what we thought was caviar but turned out to be something tangy and fresh and not caviar-like at all - we both thought some sort of berry, but we’re not sure. I regret not asking. This pintxo was as complex as it was beautiful.

Jess discovered txakoli during this trip - her search for perfectly refreshing white wines continuing apace after Italian vernaccia and vermentino two years ago. Txakoli is a simple, relatively low-alcohol wine that is consumed fresh. It has only a whisper of body filling out a brightly acidic, delicately porcelain structure. It is thrown into a glass using a special pouring modification, like Basque cider, and also like the cider, it is the perfect accompaniment to Basque food.

We stayed at a hotel in Madrid near the museums for our last night before flying out on Easter Sunday. One of the bellmen there spoke perfectly unaccented English and Jess asked him if he was from the US. He said he was, his dad was Spanish but he grew up in New Hampshire. “I usually tell people “Boston” but you guys know about New Hampshire. Nashua, actually.” And he pulled out his New Hampshire driver’s license as if we needed proof. When he hailed a cab for us on Sunday morning I thanked him and tipped him a few Euros. He said, “Muchas gracias caballero!” and I said “¡Eres la leche Nashua! ¡Buena suerte con todo!”

If you want to read about our beer experience, and see more pintxos, check out this post.

You wish you threw that milk slang

Ha!